Trash talk: truth behind food waste

Food waste can be hard to control when the quality of food is questionable.

April 6, 2023

Bees by the trash can, seagulls in the air, crows everywhere, and some need to care.

According to a report by the World Wildlife Fund, it is estimated that there is 530,000 tons of food waste per year in schools. The issue of food waste permeates throughout America and shows no sign of slowing down anytime soon.

WWF is involved with food waste because of farming’s impact on the environment. Around the world, people waste 40 percent of the food produced.

“The food we lose on farms alone could feed the world’s undernourished population almost four times over,” WWF’s website noted, “Wasted food represents roughly 10 percent of global greenhouse gas emissions (nearly four times larger than the global airline industry’s), and is a main driver of the loss of forests, grasslands, and other critical wildlife habitats—while also depleting our freshwater supply.”

According to Earth.org, fruits and vegetables are wasted the most. The waste of fruits and veggies could represent up to 50 percent of the food waste on a student’s plate, according to findings published in the Journal of Cleaner Production. These statistics are also roughly similar across American schools and even extends into American colleges (although to a lesser degree).

Although it is hard to get a definitive reason for the food waste, a great deal of insight can be gained from students.

“I don’t really think it makes sense for school to make us get… juices and fruits and milk,” said junior Ashley Furtado, referring to students having to get a juice or fruit with their entrée at school. “We eat at least some of the food but everything else we throw out.” Evidence of this can be seen on top of any garbage bin after breakfast when there are piles of juices and fruits.

Since COVID, schools have been offering free breakfast and lunch only if the student takes the complete meal. Ala carte items have to be paid for individually. The “all or nothing” approach could also be leading to more food waste since students will take a tray of food even if they are not going to eat all of it just to get a free meal.

The quality of food could also be a contributing factor to the waste issue.

“The school food here isn’t the best quality,” noted senior Alina Nguyen in a text. “The breakfast lacks nutrition; who gives out Pop Tarts?” She followed her statement with a “💀.”

According to a Penn State professor, Nguyen may be on to something.

“There are certain foods cafeteria managers are buying, presumably to meet U.S. Department of Agriculture guidelines, that the kids never are going to eat,” noted Christine Costello, an assistant professor of agricultural and biological engineering at the College of Agricultural Sciences.

This gives further credence to the fact that a recurring problem is forcing particular foods to go on a student’s plate.

With that being said, now comes the problem of actually stopping the food waste. The U.S. Department of Agriculture guidelines aren’t going away but one article from South Dakota State University, Food Waste in Schools and Strategies to Reduce It, said that a salad bar could help to reduce the amount of food discarded because “when students are able to pick the food items that they will be eating, there is less waste created.”

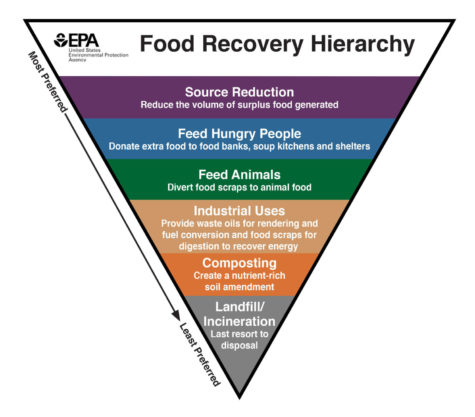

One big “solution” might also lie with the Food Recovery Hierarchy by the United States Environmental Protection Agency (EPA). This upside down pyramid shows how communities can handle food waste productively rather than allowing it to rot in a landfill.

The lowest level, Landfill/Incineration, is the level which communities want to avoid. The second level from the bottom consists of composting. This, however, isn’t often available in small, urban environments. The third level from the bottom is for industrial waste which could benefit the environment by converting food waste into fuel. The next level is feeding waste to animals which could help lower the cost of raising livestock. The second level from the top would take any excess food and feed those who are food insecure, whom, according to USDA, equates to 34 million people, 9 million of which are children. The best solution, and the top level, would be simply to reduce the amount of food actually distributed.

Overall, food waste has proven to be a mounting problem in the US. Not only would a reduction of school food waste be extremely helpful to the overall problem, but education on food waste could change the momentum of the problem for the better.